Alain Sauret sits at his desk flipping through a photo album, his piercing brown eyes looking over each image in great detail.

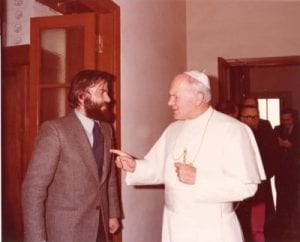

“This is when I met Paul VI,” he says. “This is John Paul II with my kids. And here’s another one of when he came by my office.”

“You can see my superiors behind the pope right outside my office—they didn’t dare try to interrupt the pope while he was talking,” Sauret says with a laugh.

Sauret has taught philosophy at Franciscan University of Steubenville since 2011, but the pictures he looks back on are evidence of a life before Franciscan, when he worked at the very heart of the Catholic Church —the Vatican.

Sauret grew up in France to a “good, Catholic family” and knew from an early age that he wanted to use his intellect to ponder the great questions of life.

“I was probably 12 or 13 when I decided that one day, I would be a philosopher,” he says.

At 14, however, Sauret lost some of the confidence he had in his faith and eventually became an existentialist. It was a few years later, after participating in a work-study program in Italy helping build the Istituto Mystici Corporis, a Catholic university, that he returned to the faith with a newfound maturity.

Returning to France after completing his studies in Italy, Sauret began studying at the University of Paris-Sorbonne, where he obtained a bachelor’s degree in philosophy in 1969, a licentiate in 1972, a master’s degree in 1975, and a doctorate in 1981.

In 1969, Sauret accepted an invitation from the leaders of the Focolare Movement, an international organization that promotes the ideals of unity and universal brotherhood, to work with young people in Rome.

“[The Focolare] made promises to live according to the social doctrine of the Church and inside of the activities, everywhere they worked,” he recalls. “I was asked to help because the Focolare was promoting some activities in favor of the population in Africa.”

While he enjoyed the work, it was volunteer and unpaid, so Sauret had to find a way to support himself. He became aware of a job opening in the Vatican to work as an Italian-to-French translator for the Congregation of Eastern Churches, a part of the Roman Curia, and was soon hired.

Pasquale Foresi, a friend of Sauret’s and one of the leaders of the Focolare Movement, offered some sage advice as his friend prepared to begin his new job.

“He said to me, ‘I know you are a Gascon, but don’t make trouble. Do whatever they ask you to do. Don’t try to understand. Do it.’ That was the best suggestion I could have received,” Sauret says.

Sauret quickly exceeded the expectations of his job as a translator, earning additional responsibilities from the congregation.

“I entered as a translator,” Sauret says, “and when you are a translator, you are aware of situations that need some adjustment, so I went to the cardinal, Paul-Pierre Philippe, telling him that there were things that should be addressed by the congregation, and he told me to work on that issue. And working on that issue, I started to coordinate financial help.”

Sauret began working on the Riunione Opere Aiuto Chiese Orientali, or Reunion of Aid Agencies to the Oriental Churches (ROACO), which sought to help the territories under the Eastern Churches in need. Churches in the Middle East, North Africa, and other countries, as well as churches of other rites, such as the Byzantine, Coptic and Armenian rites, received financial aid from ROACO.

His role was primarily coordinating the distribution of funds raised from the United States and several European countries. His office never handled the money, he notes, but made sure the funds found their proper home.

“Soon, it was a very large role, entailing more than $400 million a year that we were fundraising,” Sauret says. “But I never saw the money. In fact, my colleagues chastised me because they said, ‘You should be raising money for us.’ But that was not my purpose.”

Sauret served as secretary of ROACO until 1984, when he became general vice-secretary of the Holy Childhood Society, an organization under the same congregation focused on fostering children’s awareness of the missionary nature of the Church.

During this time period, Sauret began teaching at the Pontifical Gregorian University and the Pontifical Institure Regina Mundi in Rome, a privilege given to him directly by Pope John Paul II.

Because of his work with ROACO, Sauret met with the pope twice a year, “sometimes personally, sometimes with other people.”

“He had a great capacity to work,” Sauret recalls, “but I was really impressed by his capacity to remember people and call them by name, even if he had only met you once.”

As a matter of fact, two of Sauret’s children were baptized by the pope.

“I was meeting with the pope’s secretary, Monsignor John Magee, and someone told him, ‘You know, he has twins,’ and Magee said, ‘Oh, I am also a twin. What do you think if the pope would baptize your kids?’

“‘Okay, I have to ask my wife,’ I said. I told my wife and she exclaimed, ‘Why didn’t you say yes immediately?’ So I took my bike and went right back to the place of the secretary—the Swiss Guard had me park the bike between two limousine—and told Monsignor Magee, and said ‘Okay, my wife agreed, so the pope will baptize them.’”

The twins weren’t fazed by having the pope baptize them, Sauret recalls. In fact, when they would be at an event the pope was also at, “they would put their head out of the car and say, ‘Where is John Paul?’

“He was like a friend for them,” Sauret recalls with a chuckle.

He also exchanged correspondence with Pope John Paul I and had occasion to meet with Pope Paul VI, who Sauret describes as having a “particular manner to look deep in you.”

“He had a deep magnitude and deep understanding,” Sauret says.

Sauret enjoyed working and teaching in the Vatican, but it was becoming impossible to raise his family in Rome because of the chaos that came with living in the city. Through his spiritual director, Sauret came in contact with a hermit who was forming a congregation for hermits in the United States. Sauret volunteered to help write the statutes for the congregation and came to visit the country with two of his sons.

“While I was in the U.S., one of my boys said, ‘Daddy, because you want to leave Rome, it could be a good idea to come to the States’ and I said, ‘Why not?’”

Sauret, his wife, and their five children moved to the United States in 1995. Sauret taught at several universities, including Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit and Duquesne University in Pittsburgh before coming to Franciscan in 2011, an experience he is immensely grateful for.

“There is a respect of the student, an esteem of the students, here,” he says. “I believe that the students here study not only for the grades, but also for their life.”

Sauret says the students at Franciscan University are better prepared and more open to receiving the truth compared to state schools.

“When you are to teach elsewhere, you have to give students the background [in theology or philosophy],” he says. “Here, people have the background. We immediately meet people who are prepared to address the issues, so it’s faster and deeper teaching here than teaching in a state university.”

While he doesn’t regret his time in the Vatican, Sauret says he doesn’t miss it.

“I am pleased I did my work at the Vatican, but usually, I am pleased with what I do now,” he says. “I was pleased then with what I did and I am pleased with what I do now.”

“Many of my students will probably be saints one day,” he adds. “I believe this place is a great place to make evangelizers, which is what the U.S. needs. … That is why I like to teach here at Franciscan University.”

This story was originally published in The Troubadour, Franciscan University’s student newspaper. Author Elisha Valladares-Cormier is a junior political science major.